Conductive Hearing Loss (CHL)

Post date: 07/10/2023

Hearing is the ability to perceive sounds. The decrease of hearing ability call hearing loss.

There are many different types of Hearing loss, but they are typically classified into three main categories:

Muffled hearing

Sudden or steady loss of hearing one ear or both ears.

Full or “stuffy” sensation in the ear

Dizziness

Ear drainage

Pain or tenderness in the ear

Difficulty hearing soft sounds

Difficulty understanding speech, especially in noisy environments

Conductive hearing loss happens when the movement of sound through the external ear or middle ear is blocked, the sound does not reach the inner ear fully.

The block your ear canal.

Causing hearing loss: the block may cause by Earwax, Foreign body in the ear

Swimmer’s ear—also called otitis externa, is an infection in the ear canal often related to water exposure, or cotton swab use.

Bony lesions also called Benign Ear Cyst (Ear and Temporal Bone Tumor)

These are non-cancerous growths of bone in the ear canal often linked with cold water swimming.

Aural atresia

Defects of the external ear canal. This is most commonly noted at birth and often seen with defects of the outer ear structure, called microtia.

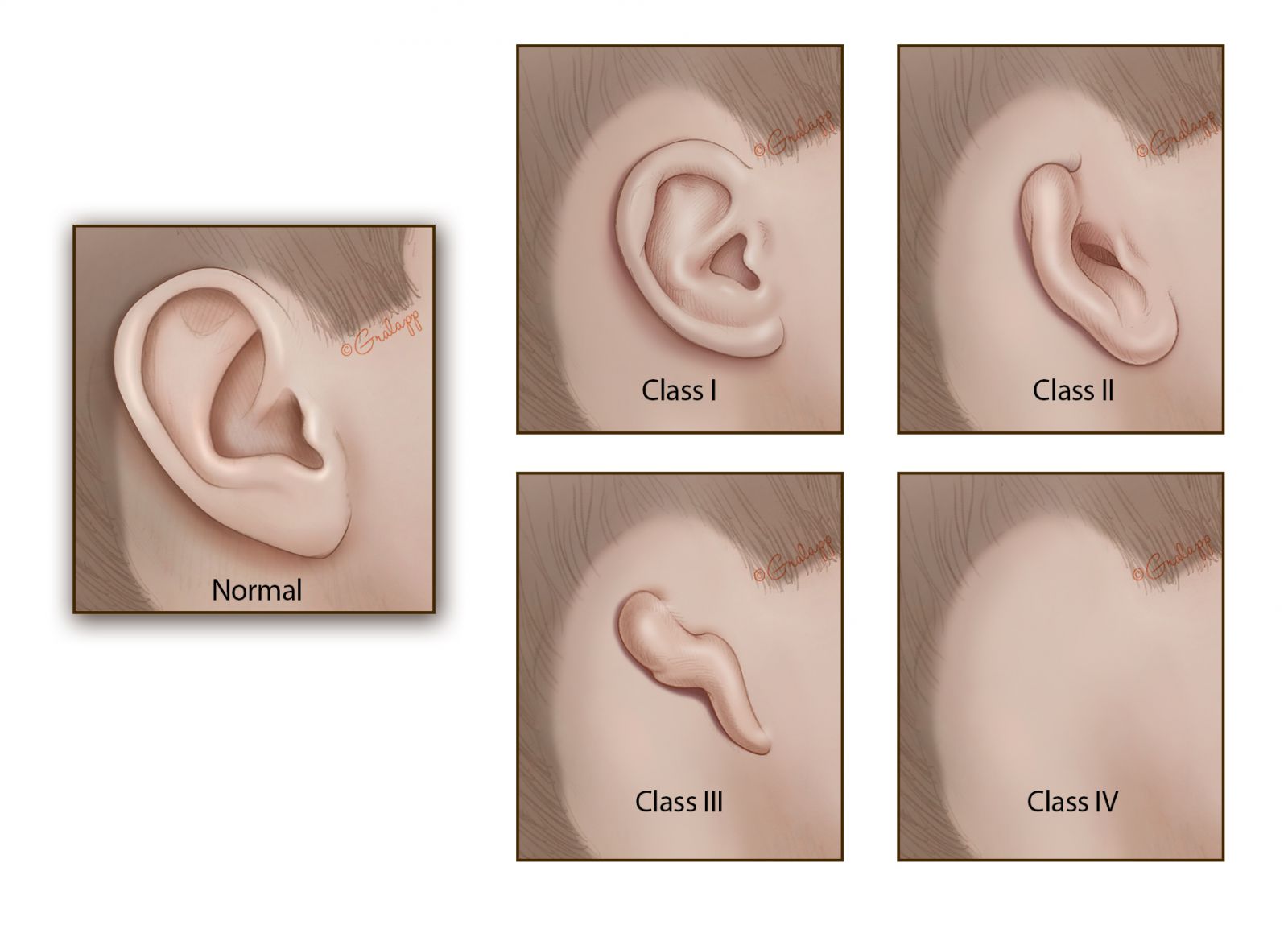

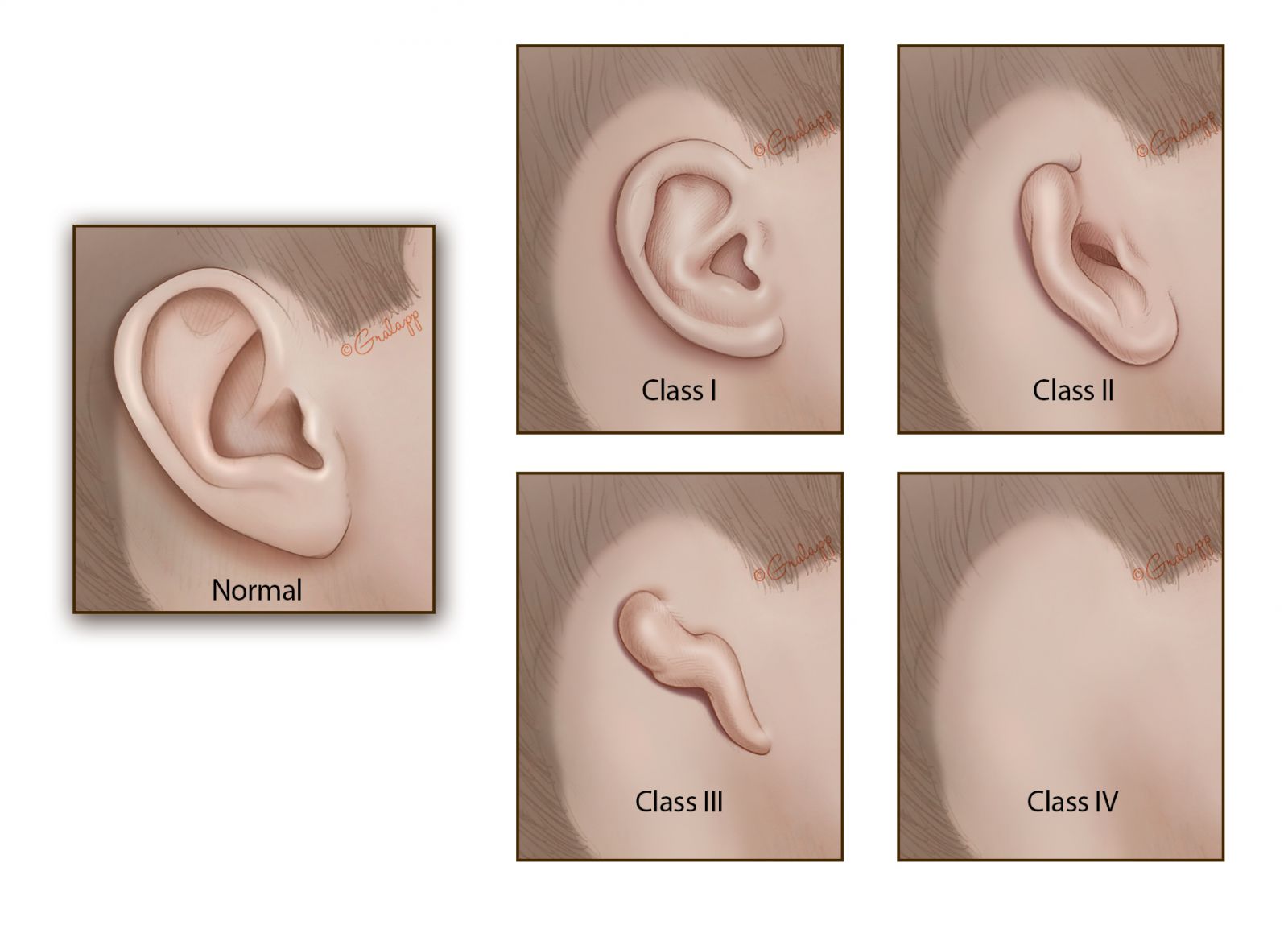

Classes of microtia:

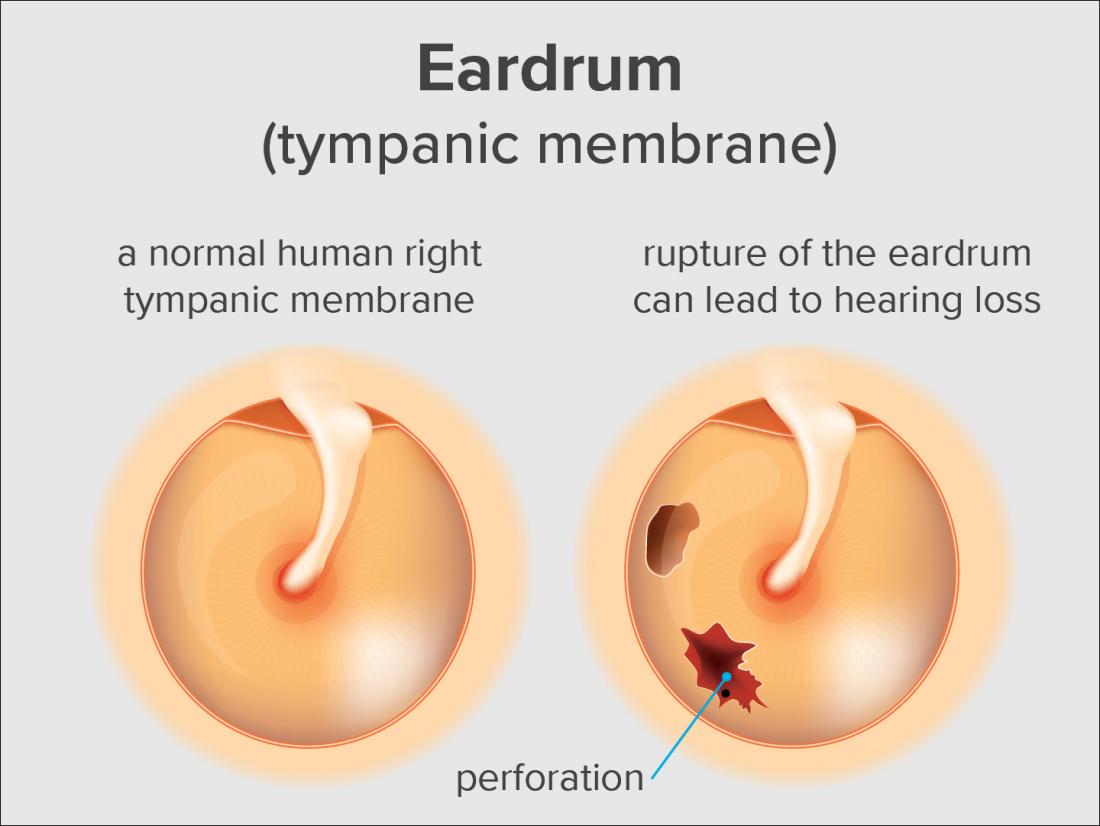

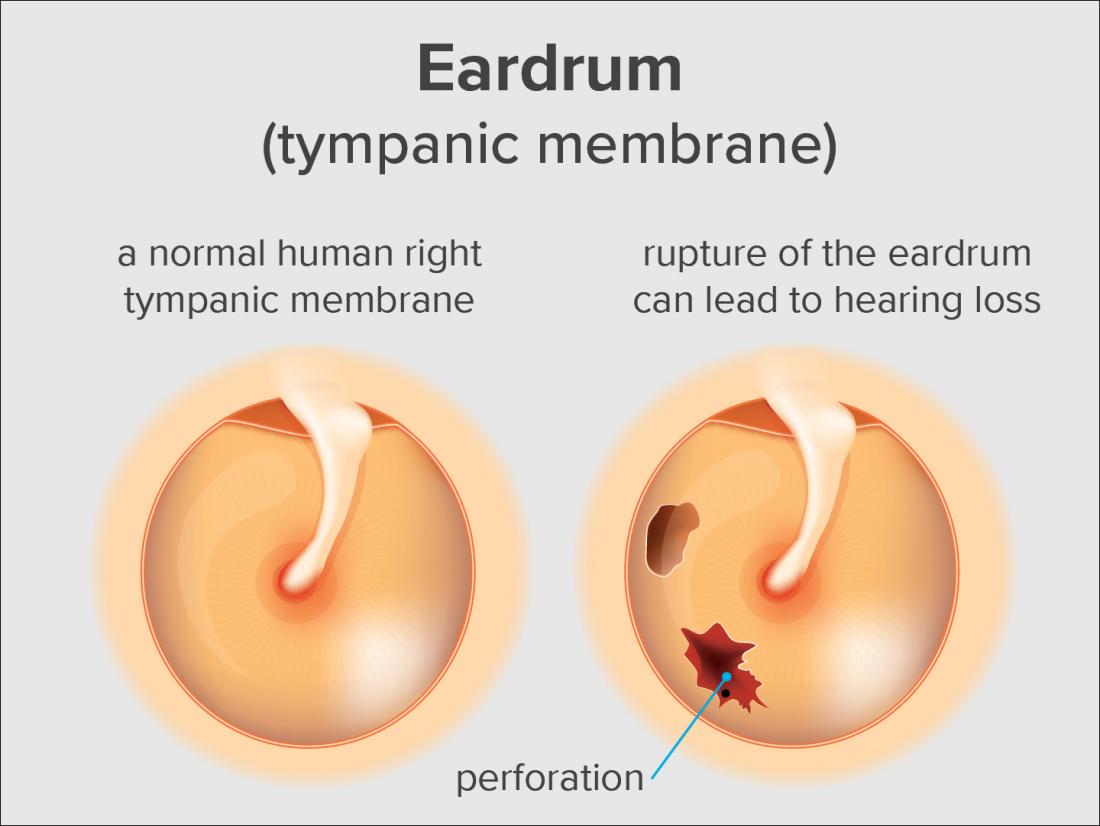

Perforation of Tympanic membrane: Eardrum problems, Perforation, rupture eardrum, also known as there is hole or tear on eardrum, that can be attributed to trauma using cotton swabs to clean the ear, barotrauma from deep water diving, or as a sequela of otitis media, or severe eustachian tube dysfunction.

Figure: the difference of normal eardrum and perforation eardrum

More commonly, problems arise at the external canal by obstruction from debris, wax, or foreign bodies.

Conductive loss associated with middle ear structures include:

Otitis media, Middle ear fluid or infection

The middle ear space normally contains air, but it can become inflamed and fluid filled (otitis media). An active infection in this area with fluid is called acute otitis media and is often painful and can cause fever. Serous otitis media is fluid in the middle ear without active infection. Both conditions are common in children.

Chronic otitis media is associated with lasting ear discharge and/or damage to the eardrum or middle ear bones (ossicles).

Eardrum collapse—called tympanic membrane retraction Severe imbalance of pressure in the middle ear can result from poor function of the Eustachian tube, causing the tympanic membrane to be pulled inward, away from the ear canal. This can happen when there is not enough air pressure in the middle ear.

Cholesteatoma

Skin cells that are present in the middle ear space that are not usually there. When skin is present in the middle ear, it is called a cholesteatoma. Cholesteatomas start small as a lump or pocket, but can grow and cause damage to the bones.

Damage to the middle ear bones

This may result from trauma, infection, cholesteatoma, or a retracted ear drum.

Otosclerosis

This is an inherited disease in which the stapes or stirrup bone in the middle ear fuses with bones around it and fails to vibrate well. It affects slightly less than one percent of the population, occurring in women more often than men.

Another study with preschool children in a South African community showed that 19% had hearing loss, with 65% of those being conductive.

They found that 9% of children had impacted cerumen, causing a hearing loss in 19% of them. In a Canadian study in school children from kindergarten to grade 6, hearing loss was found in 19%, with 93% of those being conductive. They found perforations of the tympanic membrane in 37% of unilateral loss and 46% in the bilateral loss.

In low-middle income countries, hearing loss secondary to otitis media can be as high as 26%.

Otosclerosis prevalence in the white population is 0.04% to 1% but increases to 5% in Asians, and is associated with bilateral hearing loss in up to 80% of cases.

In the elderly population, hearing loss is mostly attributed to presbycusis, which is sensorineural.

A conductive hearing loss can manifest as inappropriate behavior or inattention in the classroom.

When obtaining the child's pertinent history, it is essential to ask about speech and language development and whether the appropriate milestones have been reached. Whether the child had preceding or recurrent upper respiratory tract infections must be ascertained, as this may suggest an otitis media with effusion.

The onset of hearing loss is another essential things in the history of children and adults include

Head Trauma, and the presence of associated symptoms such as vertigo, otorrhoea, otalgia, and facial weakness.

In the older patient, It would be prudent to ask about nasal discharge and weight loss indicating a postnasal space tumor.

A child with a history of otitis media during the first two-three years of life is at risk for a mild-to-moderate conductive hearing loss affecting phonological production.

They can have difficulty perceiving strident or high-frequency consonants, such as sibilants. During speech they typically fail to produce these consonants, since they do not perceive them. This failure of sound production is called stridency deletion.

Family history and birth history to exclude any familial syndromes.

Otosclerosis has an autosomal dominant with an incomplete penetrance mode of inheritance. It usually presents in the third decade of life and is twice as common in women as men. It has a gradual onset, and the hearing loss is bilateral in 80% of cases. The patient with otosclerosis may comment that their hearing is better with background noise (paracusis Willisii). This phenomenon can occur as well in other causes of conductive hearing loss.

A full otolaryngology examination is mandatory for patients with hearing loss. Both ears must be examined with an otoscope or microscope. The examiner can see an obstruction of the ear canal with cerumen, debris, or a foreign body. Stenosis of the canal, which may be congenital or the consequence of repeated infections, can be seen. The tympanic membranes must be visualized to exclude acute infections, effusions, perforations, hemotympanum, or the presence of a cholesteatoma. Approximately 90% of patients with otosclerosis have normal tympanic membranes, while 10% have a pink tinge called Schwartz’s sign. If an adult is noted to have an effusion, then a flexible nasoendoscopy should be performed in the clinic to view the postnasal space

Weber and Rinne tuning fork tests are useful screening tests, which can be carried out in the clinic to see whether hearing loss is conductive or sensorineural. They are better suited for unilateral hearing loss and when the hearing loss is not of the mixed type. Cases of bilateral hearing loss or mixed hearing losses are better assessed using pure tone audiometry rather than tuning fork tests. To perform the Weber test, a 512Hz tuning fork is struck on the clinician's knee or elbow, and the vibrating fork is placed in the vertex of the patient’s head of the midline of the forehead. A normal result is a tuning fork being heard equally in both ears. In a conductive hearing loss, the tuning fork will be heard louder in the affected ear. In a sensorineural hearing loss, the tuning fork will be heard louder in the unaffected ear. This is used in conjunction with the Rinne test, where again a vibrating 512Hz tuning fork is placed, this time on the mastoid process until the patient can no longer hear it, and then 1cm away from the external acoustic meatus. A normal result is when air conduction is heard better than bone conduction (paradoxically called Rinne positive). If bone conduction is superior to air conduction (Rinne negative), a conductive hearing loss is present.

Evaluation

Pure tone audiometry is the mainstay of investigations for hearing loss. It can confirm the presence of hearing loss, quantify the severity, and determine the nature of the hearing loss.

Headphones deliver sounds in varying loudness over 250 to 8000 Hz. The patient notifies the audiologist when they hear the sounds 50% of the time. This is a measure of the air conduction threshold and is recorded in decibels (dB). The bone conduction threshold is determined by placing a transducer on the mastoid process. An air-bone gap exists when bone conduction is superior to air conduction. This is significant when the gap is over 10dB and marks a conductive hearing loss. Usually, an air-bone gap over 40dB indicates pathology within the ossicular chain rather than solely a tympanic membrane pathology. A Carhart notch is where there is a depression in bone conduction of around 10 to 15dB at 2kHz. This is indicative of stapes fixation, as seen in otosclerosis.

Pure tone audiometry is suitable for patients over four years old. For younger children, there are alternative tests such as play and visual reinforcement audiometry. These are all subjective hearing tests. Acoustic impedance audiometry, also called tympanometry, provides some objective evidence for the examination. Tympanometry generates a graph of the tympanic membrane's compliance and gives useful information about the middle ear pressures.

The work-up for a patient with a suspected cholesteatoma should include a computed tomographic scan of the petrous temporal bones. Brain and cervical magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium may be subsequently recommended to exclude tumor pathologies of the posterior fossa, temporal bone, and neck/oropharynx areas.

Treatment / Management

The treatment of conductive hearing loss is dependent on the underlying condition.

Any foreign body should be removed under direct visualization, with the aid of a microscope if required.

Wax and debris which is obstructing the ear canal should be amenable to micro-suction.

Perforations of the tympanic membrane often heal independently and only require a clinic follow-up evaluation in 6-8 weeks to ensure total healing. If the perforation has not sealed, then a myringoplasty may be necessary; however, the hearing effects are somewhat more unpredictable.

Otitis media with effusion usually resolves by itself and can just be monitored every three months. However, if persistent bilateral otitis media with effusion occurs over three months, and the hearing loss in the better ear is over 25-30dB, grommet insertion may be valuable. Grommets enable ventilation of the middle ear to the external auditory canal, rather than ventilating to the nasopharynx via the Eustachian tubes. A myringotomy is performed, and any middle ear fluid is suctioned out before a grommet is placed in the anteroinferior quadrant. Adenoidectomy can also be performed if there is associated hearing loss with the effusions.

The most common complications of grommets are infections and rarely tympanosclerosis. Grommets are favored to tympanostomy tubes (T-tubes) as the latter have higher rates of complications

Cholesteatomas require complete surgical excision. The two main approaches to a mastoidectomy are canal wall down, which involves an endaural or postaural incision, or canal wall up, which involves a postauricular incision.

Trauma resulting in ossicle discontinuity may require an ossiculoplasty.

Management options for otosclerosis include conservative measures such as watchful waiting, hearing aids, and fluoride supplementation.

Surgery may be indicated when the air-bone gap is over 20 dB and involve total/partial stapedectomy or stapedotomy.

Conductive hearing loss that is not amenable to medical or surgical management can be treated with hearing aids. There are various types: air conduction hearing aids, bone conduction hearing aids, and bone-anchored hearing aids.

The treatment options can include:

Observation with repeat hearing testing at a subsequent follow up visit

Evaluation and fitting of a hearing aid(s) and other assistive listening devices

Preferential seating in class for school children

Surgery to address the cause of hearing loss

Surgery to implant a hearing device

These conditions may not, but likely will, need surgery:

Cholesteatoma

Bony lesions

Aural atresia

Otitis media (if chronic or recurrent)

Severe retraction of the tympanic membrane

A hole in the ear drum

Damage to the middle ear bones

Otosclerosis

Many types of hearing loss can also be treated with the use of conventional hearing or an implantable hearing device. Again, your ENT specialist and/or audiologist can help you decide which device may work best for you and your lifestyle.

Defect in the pinna, external auditory canal, tympanic membrane, and ossicles

Aural atresia

External canal obstruction

Tympanic membrane perforation

Acute otitis media

Otitis media with effusion

Nasopharyngeal tumor

Cholesteatoma

Otosclerosis

Ossicle discontinuity after head trauma

Simple conditions such as wax impaction and otitis media with effusion have excellent outcomes.

Conductive hearing loss in children can lead to disastrous speech and language delays and impact their education if not promptly diagnosed and treated.

Cholesteatomas can have significant invasion and destruction of local structures.

Some conditions causing conductive hearing loss will produce a permanent hearing loss if untreated.

Hearing aids can be highly effective in cases when hearing loss is not treatable.

Parents and teachers must be aware that misbehavior or inattention of childdren at school can be a sign of hearing loss, and prompt diagnosis can prevent speech and language delays.

You should be instructed not to insert sharp objects into ear intent to clean the ear.

When use of cotton swabs should be restricted to the most outer part of the external ear canal. Cotton swabs can push the wax deeper into the ear canal.

In most cases, cleaning the ear canal should not be done with a cotton swab as the wax usually falls out on its own.

Thank you

By. Dr. Nguyen T. N. Minh

References

4.Abdel-Aziz M. Congenital aural atresia. J Craniofac Surg. 2013 Jul;24(4):e418-22. [PubMed]

5.Sogebi OA, Oyewole EA, Manifah TO, Ogunbanwo O. Hearing dynamics in patients with traumatic tympanic membrane perforation. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2017 Apr-Jun;7(2):15-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

6.Coleman A, Cervin A. Probiotics in the treatment of otitis media. The past, the present and the future. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 Jan;116:135-140. [PubMed]

7.Mills R, Hathorn I. Aetiology and pathology of otitis media with effusion in adult life. J Laryngol Otol. 2016 May;130(5):418-24. [PubMed]

8.Kuo CL, Shiao AS, Yung M, Sakagami M, Sudhoff H, Wang CH, Hsu CH, Lien CF. Updates and knowledge gaps in cholesteatoma research. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:854024. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

9.Quesnel AM, Ishai R, McKenna MJ. Otosclerosis: Temporal Bone Pathology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018 Apr;51(2):291-303. [PubMed]

10.Khairi Md Daud M, Noor RM, Rahman NA, Sidek DS, Mohamad A. The effect of mild hearing loss on academic performance in primary school children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010 Jan;74(1):67-70. [PubMed]

11.Yousuf Hussein S, Swanepoel W, Mahomed-Asmail F, de Jager LB. Hearing loss in preschool children from a low income South African community. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018 Dec;115:145-148. [PubMed]

12.Fitzpatrick EM, McCurdy L, Whittingham J, Rourke R, Nassrallah F, Grandpierre V, Momoli F, Bijelic V. Hearing loss prevalence and hearing health among school-aged children in the Canadian Arctic. Int J Audiol. 2021 Jul;60(7):521-531. [PubMed]

13.Leach AJ, Homøe P, Chidziva C, Gunasekera H, Kong K, Bhutta MF, Jensen R, Tamir SO, Das SK, Morris P. Panel 6: Otitis media and associated hearing loss among disadvantaged populations and low to middle-income countries. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Mar;130 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):109857. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

14.Markou K, Goudakos J. An overview of the etiology of otosclerosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009 Jan;266(1):25-35. [PubMed]

15.Yamasoba T, Lin FR, Someya S, Kashio A, Sakamoto T, Kondo K. Current concepts in age-related hearing loss: epidemiology and mechanistic pathways. Hear Res. 2013 Sep;303:30-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

16.Venekamp RP, Burton MJ, van Dongen TM, van der Heijden GJ, van Zon A, Schilder AG. Antibiotics for otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jun 12;2016(6):CD009163. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

17.Crompton M, Cadge BA, Ziff JL, Mowat AJ, Nash R, Lavy JA, Powell HRF, Aldren CP, Saeed SR, Dawson SJ. The Epidemiology of Otosclerosis in a British Cohort. Otol Neurotol. 2019 Jan;40(1):22-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

18.Salomone R, Riskalla PE, Vicente Ade O, Boccalini MC, Chaves AG, Lopes R, Felin Filho GB. Pediatric otosclerosis: case report and literature review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008 Mar-Apr;74(2):303-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

19.Cunniffe HA, Gona AK, Phillips JS. Should adults with isolated serous otitis media be undergoing routine biopsies of the post-nasal space? J Laryngol Otol. 2020 Sep 10;:1-3. [PubMed]

20.Bayoumy AB, de Ru JA. Sudden deafness and tuning fork tests: towards optimal utilisation. Pract Neurol. 2020 Feb;20(1):66-68. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

21.Musiek FE, Shinn J, Chermak GD, Bamiou DE. Perspectives on the Pure-Tone Audiogram. J Am Acad Audiol. 2017 Jul/Aug;28(7):655-671. [PubMed]

22.Wiatr M, Wiatr A, Składzień J, Stręk P. Determinants of Change in Air-Bone Gap and Bone Conduction in Patients Operated on for Chronic Otitis Media. Med Sci Monit. 2015 Aug 11;21:2345-51. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

23.Wiatr A, Składzień J, Strek P, Wiatr M. Carhart Notch-A Prognostic Factor in Surgery for Otosclerosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021 May;100(4):NP193-NP197. [PubMed]

24.Parlea E, Georgescu M, Calarasu R. Tympanometry as a predictor factor in the evolution of otitis media with effusion. J Med Life. 2012 Dec 15;5(4):452-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

25. Grigg S, Grigg C. Removal of ear, nose and throat foreign bodies: A review. Aust J Gen Pract. 2018 Oct;47(10):682-685. [PubMed]

26. Sogebi OA, Oyewole EA, Mabifah TO. Traumatic tympanic membrane perforations: characteristics and factors affecting outcome. Ghana Med J. 2018 Mar;52(1):34-40. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

27. Rovers MM, Black N, Browning GG, Maw R, Zielhuis GA, Haggard MP. Grommets in otitis media with effusion: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2005 May;90(5):480-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

28. Gates GA, Avery CA, Prihoda TJ, Cooper JC. Effectiveness of adenoidectomy and tympanostomy tubes in the treatment of chronic otitis media with effusion. N Engl J Med. 1987 Dec 03;317(23):1444-51. [PubMed]

29. Kay DJ, Nelson M, Rosenfeld RM. Meta-analysis of tympanostomy tube sequelae. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):374-80. [PubMed]

30. Karamert R, Eravcı FC, Cebeci S, Düzlü M, Zorlu ME, Gülhan N, Tutar H, Uğur MB, İriz A, Bayazıt YA. Canal wall down versus canal wall up surgeries in the treatment of middle ear cholesteatoma. Turk J Med Sci. 2019 Oct 24;49(5):1426-1432. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

31. Cheng HCS, Agrawal SK, Parnes LS. Stapedectomy Versus Stapedotomy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018 Apr;51(2):375-392. [PubMed]

32. Wright T. Ear wax. BMJ Clin Evid. 2015 Mar 04;2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

33. Atkinson H, Wallis S, Coatesworth AP. Otitis media with effusion. Postgrad Med. 2015 May;127(4):381-5. [PubMed]

34. Kozlowski L, Ribas A, Almeida G, Luz I. Satisfaction of Elderly Hearing Aid Users. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jan;21(1):92-96. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

35. Ferguson MA, Kitterick PT, Chong LY, Edmondson-Jones M, Barker F, Hoare DJ. Hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Sep 25;9(9):CD012023. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

36. Tomblin JB, Oleson JJ, Ambrose SE, Walker E, Moeller MP. The influence of hearing aids on the speech and language development of children with hearing loss. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 May;140(5):403-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

keywords: Conductive hearing loss, Hearing loss, Degrees of Hearing Loss, Normal hearing, Sensorineural Hearing Loss (SNHL), Difficulty hearing soft sounds, dizziness, presbycusis, age-related hearing loss, noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL), meniere's disease, autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED),

There are many different types of Hearing loss, but they are typically classified into three main categories:

- Conductive hearing loss occurs when there is a problem with the outer or middle ear, which blocks sound from reaching the inner ear. This type of hearing loss can be caused by earwax buildup, ear infections, or damage to the eardrum or bones of the middle ear.

- Sensorineural hearing loss occurs when there is damage to the inner ear or the auditory nerve, which sends sound signals to the brain. This type of hearing loss is often caused by aging, noise exposure, or certain diseases, such as Meniere's disease.

- Mixed hearing loss is a combination of conductive and sensorineural hearing loss. This type of hearing loss can be caused by a combination of factors, such as earwax buildup and age-related hearing loss.

In addition to these three main categories, there are also other types of hearing loss, such as:

- Central hearing loss occurs when there is a problem with the way the brain interprets sound signals. This type of hearing loss is rare and can be caused by certain diseases, such as stroke or multiple sclerosis.

- Functional hearing loss is a type of hearing loss that is not caused by any physical damage to the ears or the auditory system. This type of hearing loss is often caused by stress, anxiety, or depression.

Symptoms of Conductive Hearing Loss

Symptoms of conductive hearing loss can vary depending on the exact cause and severity, but may include or be associated with:Muffled hearing

Sudden or steady loss of hearing one ear or both ears.

Full or “stuffy” sensation in the ear

Dizziness

Ear drainage

Pain or tenderness in the ear

Difficulty hearing soft sounds

Difficulty understanding speech, especially in noisy environments

Conductive hearing loss happens when the movement of sound through the external ear or middle ear is blocked, the sound does not reach the inner ear fully.

Etiology - Cause of conductive hearing loss.

Conductive hearing loss is caused by a problem in the outer or middle ear that prevents sound waves from reaching the inner ear. The most common causes of conductive hearing loss include:The block your ear canal.

Causing hearing loss: the block may cause by Earwax, Foreign body in the ear

Swimmer’s ear—also called otitis externa, is an infection in the ear canal often related to water exposure, or cotton swab use.

Bony lesions also called Benign Ear Cyst (Ear and Temporal Bone Tumor)

These are non-cancerous growths of bone in the ear canal often linked with cold water swimming.

Aural atresia

Defects of the external ear canal. This is most commonly noted at birth and often seen with defects of the outer ear structure, called microtia.

Classes of microtia:

Microtia is a congenital condition in which the external ear is underdeveloped or absent. It can affect one or both ears. There are four main classes of microtia, ranging from mild to severe:

- Grade I: The ear is smaller than normal but has all of the usual features.

- Grade II: The ear is smaller and some of the features are missing, but the lower two-thirds of the ear is usually present.

- Grade III: This is the most common type of microtia. The ear is very small and only the earlobe is usually present.

- Grade IV: The ear is completely absent (anotia).

Perforation of Tympanic membrane: Eardrum problems, Perforation, rupture eardrum, also known as there is hole or tear on eardrum, that can be attributed to trauma using cotton swabs to clean the ear, barotrauma from deep water diving, or as a sequela of otitis media, or severe eustachian tube dysfunction.

Figure: the difference of normal eardrum and perforation eardrum

More commonly, problems arise at the external canal by obstruction from debris, wax, or foreign bodies.

Conductive loss associated with middle ear structures include:

Otitis media, Middle ear fluid or infection

The middle ear space normally contains air, but it can become inflamed and fluid filled (otitis media). An active infection in this area with fluid is called acute otitis media and is often painful and can cause fever. Serous otitis media is fluid in the middle ear without active infection. Both conditions are common in children.

Chronic otitis media is associated with lasting ear discharge and/or damage to the eardrum or middle ear bones (ossicles).

Eardrum collapse—called tympanic membrane retraction Severe imbalance of pressure in the middle ear can result from poor function of the Eustachian tube, causing the tympanic membrane to be pulled inward, away from the ear canal. This can happen when there is not enough air pressure in the middle ear.

Cholesteatoma

Skin cells that are present in the middle ear space that are not usually there. When skin is present in the middle ear, it is called a cholesteatoma. Cholesteatomas start small as a lump or pocket, but can grow and cause damage to the bones.

Damage to the middle ear bones

This may result from trauma, infection, cholesteatoma, or a retracted ear drum.

Otosclerosis

This is an inherited disease in which the stapes or stirrup bone in the middle ear fuses with bones around it and fails to vibrate well. It affects slightly less than one percent of the population, occurring in women more often than men.

Epidemiology of conductive hearing loss

Conductive hearing loss is common in younger patients due to conditions such as otitis media with effusion. A study on primary school children found the prevalence of hearing loss to be 15%, with 88.9% of those being conductive.Another study with preschool children in a South African community showed that 19% had hearing loss, with 65% of those being conductive.

They found that 9% of children had impacted cerumen, causing a hearing loss in 19% of them. In a Canadian study in school children from kindergarten to grade 6, hearing loss was found in 19%, with 93% of those being conductive. They found perforations of the tympanic membrane in 37% of unilateral loss and 46% in the bilateral loss.

In low-middle income countries, hearing loss secondary to otitis media can be as high as 26%.

Otosclerosis prevalence in the white population is 0.04% to 1% but increases to 5% in Asians, and is associated with bilateral hearing loss in up to 80% of cases.

In the elderly population, hearing loss is mostly attributed to presbycusis, which is sensorineural.

History and Physical

A thorough history can point towards the cause of the hearing loss.A conductive hearing loss can manifest as inappropriate behavior or inattention in the classroom.

When obtaining the child's pertinent history, it is essential to ask about speech and language development and whether the appropriate milestones have been reached. Whether the child had preceding or recurrent upper respiratory tract infections must be ascertained, as this may suggest an otitis media with effusion.

The onset of hearing loss is another essential things in the history of children and adults include

Head Trauma, and the presence of associated symptoms such as vertigo, otorrhoea, otalgia, and facial weakness.

In the older patient, It would be prudent to ask about nasal discharge and weight loss indicating a postnasal space tumor.

A child with a history of otitis media during the first two-three years of life is at risk for a mild-to-moderate conductive hearing loss affecting phonological production.

They can have difficulty perceiving strident or high-frequency consonants, such as sibilants. During speech they typically fail to produce these consonants, since they do not perceive them. This failure of sound production is called stridency deletion.

Family history and birth history to exclude any familial syndromes.

Otosclerosis has an autosomal dominant with an incomplete penetrance mode of inheritance. It usually presents in the third decade of life and is twice as common in women as men. It has a gradual onset, and the hearing loss is bilateral in 80% of cases. The patient with otosclerosis may comment that their hearing is better with background noise (paracusis Willisii). This phenomenon can occur as well in other causes of conductive hearing loss.

A full otolaryngology examination is mandatory for patients with hearing loss. Both ears must be examined with an otoscope or microscope. The examiner can see an obstruction of the ear canal with cerumen, debris, or a foreign body. Stenosis of the canal, which may be congenital or the consequence of repeated infections, can be seen. The tympanic membranes must be visualized to exclude acute infections, effusions, perforations, hemotympanum, or the presence of a cholesteatoma. Approximately 90% of patients with otosclerosis have normal tympanic membranes, while 10% have a pink tinge called Schwartz’s sign. If an adult is noted to have an effusion, then a flexible nasoendoscopy should be performed in the clinic to view the postnasal space

Weber and Rinne tuning fork tests are useful screening tests, which can be carried out in the clinic to see whether hearing loss is conductive or sensorineural. They are better suited for unilateral hearing loss and when the hearing loss is not of the mixed type. Cases of bilateral hearing loss or mixed hearing losses are better assessed using pure tone audiometry rather than tuning fork tests. To perform the Weber test, a 512Hz tuning fork is struck on the clinician's knee or elbow, and the vibrating fork is placed in the vertex of the patient’s head of the midline of the forehead. A normal result is a tuning fork being heard equally in both ears. In a conductive hearing loss, the tuning fork will be heard louder in the affected ear. In a sensorineural hearing loss, the tuning fork will be heard louder in the unaffected ear. This is used in conjunction with the Rinne test, where again a vibrating 512Hz tuning fork is placed, this time on the mastoid process until the patient can no longer hear it, and then 1cm away from the external acoustic meatus. A normal result is when air conduction is heard better than bone conduction (paradoxically called Rinne positive). If bone conduction is superior to air conduction (Rinne negative), a conductive hearing loss is present.

Evaluation

Pure tone audiometry is the mainstay of investigations for hearing loss. It can confirm the presence of hearing loss, quantify the severity, and determine the nature of the hearing loss.

Headphones deliver sounds in varying loudness over 250 to 8000 Hz. The patient notifies the audiologist when they hear the sounds 50% of the time. This is a measure of the air conduction threshold and is recorded in decibels (dB). The bone conduction threshold is determined by placing a transducer on the mastoid process. An air-bone gap exists when bone conduction is superior to air conduction. This is significant when the gap is over 10dB and marks a conductive hearing loss. Usually, an air-bone gap over 40dB indicates pathology within the ossicular chain rather than solely a tympanic membrane pathology. A Carhart notch is where there is a depression in bone conduction of around 10 to 15dB at 2kHz. This is indicative of stapes fixation, as seen in otosclerosis.

Pure tone audiometry is suitable for patients over four years old. For younger children, there are alternative tests such as play and visual reinforcement audiometry. These are all subjective hearing tests. Acoustic impedance audiometry, also called tympanometry, provides some objective evidence for the examination. Tympanometry generates a graph of the tympanic membrane's compliance and gives useful information about the middle ear pressures.

The work-up for a patient with a suspected cholesteatoma should include a computed tomographic scan of the petrous temporal bones. Brain and cervical magnetic resonance imaging with gadolinium may be subsequently recommended to exclude tumor pathologies of the posterior fossa, temporal bone, and neck/oropharynx areas.

Treatment Options for Conductive hearing loss

If you are experiencing hearing loss, you should see an ENT (ear, nose, and throat) specialist, or otolaryngologist, who can make a specific diagnosis for you, and talk to you about treatment options, including surgical procedures.Treatment / Management

The treatment of conductive hearing loss is dependent on the underlying condition.

Any foreign body should be removed under direct visualization, with the aid of a microscope if required.

Wax and debris which is obstructing the ear canal should be amenable to micro-suction.

Perforations of the tympanic membrane often heal independently and only require a clinic follow-up evaluation in 6-8 weeks to ensure total healing. If the perforation has not sealed, then a myringoplasty may be necessary; however, the hearing effects are somewhat more unpredictable.

Otitis media with effusion usually resolves by itself and can just be monitored every three months. However, if persistent bilateral otitis media with effusion occurs over three months, and the hearing loss in the better ear is over 25-30dB, grommet insertion may be valuable. Grommets enable ventilation of the middle ear to the external auditory canal, rather than ventilating to the nasopharynx via the Eustachian tubes. A myringotomy is performed, and any middle ear fluid is suctioned out before a grommet is placed in the anteroinferior quadrant. Adenoidectomy can also be performed if there is associated hearing loss with the effusions.

The most common complications of grommets are infections and rarely tympanosclerosis. Grommets are favored to tympanostomy tubes (T-tubes) as the latter have higher rates of complications

Cholesteatomas require complete surgical excision. The two main approaches to a mastoidectomy are canal wall down, which involves an endaural or postaural incision, or canal wall up, which involves a postauricular incision.

Trauma resulting in ossicle discontinuity may require an ossiculoplasty.

Management options for otosclerosis include conservative measures such as watchful waiting, hearing aids, and fluoride supplementation.

Surgery may be indicated when the air-bone gap is over 20 dB and involve total/partial stapedectomy or stapedotomy.

Conductive hearing loss that is not amenable to medical or surgical management can be treated with hearing aids. There are various types: air conduction hearing aids, bone conduction hearing aids, and bone-anchored hearing aids.

The treatment options can include:

Observation with repeat hearing testing at a subsequent follow up visit

Evaluation and fitting of a hearing aid(s) and other assistive listening devices

Preferential seating in class for school children

Surgery to address the cause of hearing loss

Surgery to implant a hearing device

These conditions may not, but likely will, need surgery:

Cholesteatoma

Bony lesions

Aural atresia

Otitis media (if chronic or recurrent)

Severe retraction of the tympanic membrane

A hole in the ear drum

Damage to the middle ear bones

Otosclerosis

Many types of hearing loss can also be treated with the use of conventional hearing or an implantable hearing device. Again, your ENT specialist and/or audiologist can help you decide which device may work best for you and your lifestyle.

Differential Diagnosis with conductive hearing loss

The differential diagnosis for conductive hearing loss is extensive. A thorough history and examination, together with pure tone audiometry, will point towards the underlying cause. It is essential to confirm that the hearing loss is conductive rather than sensorineural, guiding subsequent investigations and management.Defect in the pinna, external auditory canal, tympanic membrane, and ossicles

Aural atresia

External canal obstruction

Tympanic membrane perforation

Acute otitis media

Otitis media with effusion

Nasopharyngeal tumor

Cholesteatoma

Otosclerosis

Ossicle discontinuity after head trauma

Prognosis - outlook for conductive hearing loss

Depending on the cause of the conductive hearing loss, the prognosis is different.Simple conditions such as wax impaction and otitis media with effusion have excellent outcomes.

Complications

The following complications may be observed:Conductive hearing loss in children can lead to disastrous speech and language delays and impact their education if not promptly diagnosed and treated.

Cholesteatomas can have significant invasion and destruction of local structures.

Some conditions causing conductive hearing loss will produce a permanent hearing loss if untreated.

Consultations

Consultations from otolaryngologists, neuro otologists, and audiologists may be required.Deterrence and Patient Education

Hearing loss can be treated mainly if it is conductive, if you think you have hearing problem you should seek medical help.Hearing aids can be highly effective in cases when hearing loss is not treatable.

Parents and teachers must be aware that misbehavior or inattention of childdren at school can be a sign of hearing loss, and prompt diagnosis can prevent speech and language delays.

You should be instructed not to insert sharp objects into ear intent to clean the ear.

When use of cotton swabs should be restricted to the most outer part of the external ear canal. Cotton swabs can push the wax deeper into the ear canal.

In most cases, cleaning the ear canal should not be done with a cotton swab as the wax usually falls out on its own.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Hearing loss is a frequent problem affecting all ages. Careful diagnosis and treatment are required in many cases to prevent further complications. A multidisciplinary approach is necessary when managing conductive hearing loss, including otolaryngologists, audiologists, general practitioners, and specialty nurses. Pediatricians should closely follow patients with otitis media for recurrent episodes and problems in school learning and performance. Recommendations from all members of the team are obtained to achieve the best possible outcome for the patient. Using evidence-based information, the best results can be obtained.Thank you

By. Dr. Nguyen T. N. Minh

References

- 1.

-

Zahnert T. The differential diagnosis of hearing loss. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2011 Jun;108(25):433-43; quiz 444. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.

-

Phan NT, McKenzie JL, Huang L, Whitfield B, Chang A. Diagnosis and management of hearing loss in elderly patients. Aust Fam Physician. 2016 Jun;45(6):366-9. [PubMed]

- 3.

-

Mamo SK, Reed NS, Price C, Occhipinti D, Pletnikova A, Lin FR, Oh ES. Hearing Loss Treatment in Older Adults With Cognitive Impairment: A Systematic Review. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 2018 Oct 26;61(10):2589-2603. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.

- 5.

-

Sogebi OA, Oyewole EA, Manifah TO, Ogunbanwo O. Hearing dynamics in patients with traumatic tympanic membrane perforation. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2017 Apr-Jun;7(2):15-30.[PMC free article] [PubMed]

4.Abdel-Aziz M. Congenital aural atresia. J Craniofac Surg. 2013 Jul;24(4):e418-22. [PubMed]

5.Sogebi OA, Oyewole EA, Manifah TO, Ogunbanwo O. Hearing dynamics in patients with traumatic tympanic membrane perforation. J West Afr Coll Surg. 2017 Apr-Jun;7(2):15-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

6.Coleman A, Cervin A. Probiotics in the treatment of otitis media. The past, the present and the future. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2019 Jan;116:135-140. [PubMed]

7.Mills R, Hathorn I. Aetiology and pathology of otitis media with effusion in adult life. J Laryngol Otol. 2016 May;130(5):418-24. [PubMed]

8.Kuo CL, Shiao AS, Yung M, Sakagami M, Sudhoff H, Wang CH, Hsu CH, Lien CF. Updates and knowledge gaps in cholesteatoma research. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:854024. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

9.Quesnel AM, Ishai R, McKenna MJ. Otosclerosis: Temporal Bone Pathology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018 Apr;51(2):291-303. [PubMed]

10.Khairi Md Daud M, Noor RM, Rahman NA, Sidek DS, Mohamad A. The effect of mild hearing loss on academic performance in primary school children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010 Jan;74(1):67-70. [PubMed]

11.Yousuf Hussein S, Swanepoel W, Mahomed-Asmail F, de Jager LB. Hearing loss in preschool children from a low income South African community. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2018 Dec;115:145-148. [PubMed]

12.Fitzpatrick EM, McCurdy L, Whittingham J, Rourke R, Nassrallah F, Grandpierre V, Momoli F, Bijelic V. Hearing loss prevalence and hearing health among school-aged children in the Canadian Arctic. Int J Audiol. 2021 Jul;60(7):521-531. [PubMed]

13.Leach AJ, Homøe P, Chidziva C, Gunasekera H, Kong K, Bhutta MF, Jensen R, Tamir SO, Das SK, Morris P. Panel 6: Otitis media and associated hearing loss among disadvantaged populations and low to middle-income countries. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2020 Mar;130 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):109857. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

14.Markou K, Goudakos J. An overview of the etiology of otosclerosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2009 Jan;266(1):25-35. [PubMed]

15.Yamasoba T, Lin FR, Someya S, Kashio A, Sakamoto T, Kondo K. Current concepts in age-related hearing loss: epidemiology and mechanistic pathways. Hear Res. 2013 Sep;303:30-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

16.Venekamp RP, Burton MJ, van Dongen TM, van der Heijden GJ, van Zon A, Schilder AG. Antibiotics for otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Jun 12;2016(6):CD009163. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

17.Crompton M, Cadge BA, Ziff JL, Mowat AJ, Nash R, Lavy JA, Powell HRF, Aldren CP, Saeed SR, Dawson SJ. The Epidemiology of Otosclerosis in a British Cohort. Otol Neurotol. 2019 Jan;40(1):22-30. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

18.Salomone R, Riskalla PE, Vicente Ade O, Boccalini MC, Chaves AG, Lopes R, Felin Filho GB. Pediatric otosclerosis: case report and literature review. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2008 Mar-Apr;74(2):303-6. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

19.Cunniffe HA, Gona AK, Phillips JS. Should adults with isolated serous otitis media be undergoing routine biopsies of the post-nasal space? J Laryngol Otol. 2020 Sep 10;:1-3. [PubMed]

20.Bayoumy AB, de Ru JA. Sudden deafness and tuning fork tests: towards optimal utilisation. Pract Neurol. 2020 Feb;20(1):66-68. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

21.Musiek FE, Shinn J, Chermak GD, Bamiou DE. Perspectives on the Pure-Tone Audiogram. J Am Acad Audiol. 2017 Jul/Aug;28(7):655-671. [PubMed]

22.Wiatr M, Wiatr A, Składzień J, Stręk P. Determinants of Change in Air-Bone Gap and Bone Conduction in Patients Operated on for Chronic Otitis Media. Med Sci Monit. 2015 Aug 11;21:2345-51. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

23.Wiatr A, Składzień J, Strek P, Wiatr M. Carhart Notch-A Prognostic Factor in Surgery for Otosclerosis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021 May;100(4):NP193-NP197. [PubMed]

24.Parlea E, Georgescu M, Calarasu R. Tympanometry as a predictor factor in the evolution of otitis media with effusion. J Med Life. 2012 Dec 15;5(4):452-4. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

25. Grigg S, Grigg C. Removal of ear, nose and throat foreign bodies: A review. Aust J Gen Pract. 2018 Oct;47(10):682-685. [PubMed]

26. Sogebi OA, Oyewole EA, Mabifah TO. Traumatic tympanic membrane perforations: characteristics and factors affecting outcome. Ghana Med J. 2018 Mar;52(1):34-40. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

27. Rovers MM, Black N, Browning GG, Maw R, Zielhuis GA, Haggard MP. Grommets in otitis media with effusion: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2005 May;90(5):480-5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

28. Gates GA, Avery CA, Prihoda TJ, Cooper JC. Effectiveness of adenoidectomy and tympanostomy tubes in the treatment of chronic otitis media with effusion. N Engl J Med. 1987 Dec 03;317(23):1444-51. [PubMed]

29. Kay DJ, Nelson M, Rosenfeld RM. Meta-analysis of tympanostomy tube sequelae. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001 Apr;124(4):374-80. [PubMed]

30. Karamert R, Eravcı FC, Cebeci S, Düzlü M, Zorlu ME, Gülhan N, Tutar H, Uğur MB, İriz A, Bayazıt YA. Canal wall down versus canal wall up surgeries in the treatment of middle ear cholesteatoma. Turk J Med Sci. 2019 Oct 24;49(5):1426-1432. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

31. Cheng HCS, Agrawal SK, Parnes LS. Stapedectomy Versus Stapedotomy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2018 Apr;51(2):375-392. [PubMed]

32. Wright T. Ear wax. BMJ Clin Evid. 2015 Mar 04;2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed]

33. Atkinson H, Wallis S, Coatesworth AP. Otitis media with effusion. Postgrad Med. 2015 May;127(4):381-5. [PubMed]

34. Kozlowski L, Ribas A, Almeida G, Luz I. Satisfaction of Elderly Hearing Aid Users. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jan;21(1):92-96. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

35. Ferguson MA, Kitterick PT, Chong LY, Edmondson-Jones M, Barker F, Hoare DJ. Hearing aids for mild to moderate hearing loss in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Sep 25;9(9):CD012023. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

36. Tomblin JB, Oleson JJ, Ambrose SE, Walker E, Moeller MP. The influence of hearing aids on the speech and language development of children with hearing loss. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014 May;140(5):403-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

keywords: Conductive hearing loss, Hearing loss, Degrees of Hearing Loss, Normal hearing, Sensorineural Hearing Loss (SNHL), Difficulty hearing soft sounds, dizziness, presbycusis, age-related hearing loss, noise-induced hearing loss (NIHL), meniere's disease, autoimmune inner ear disease (AIED),